So you went to puppy or basic obedience class with your new dog and you learned the basics of “stay.” Your dog did a really good job at staying for 5 – 10 seconds while you rewarded him frequently.

But how do you get to a 10-minute “down stay,” with you out of sight? What about staying while you open the front door or remaining in place when a cat races by?

Strengthening your dog’s stay can feel daunting and can undo all your foundational work if done incorrectly. Below are a few tips to help your dog have a great stay in any circumstance.

There are three components to stay: distance (from you), duration (time in the stay), and distractions (can my dog stay while kids run around him or a ball is thrown?)

Basic Tips

- At first, you only want to work on one component (duration, distance, or distraction) at a time. This means, at the beginning, you need to work on your stays in a quiet room of the house, not outside where there will be distractions you can’t control – like wildlife.

- Don’t stare at your dog the whole time! This can make some fidgety, and for others, it can become part of the “stay” cue. You don’t want your dog to only stay because you are staring at him.

- If your dog breaks his stay, put him calmly and nicely back into position but don’t reward immediately. You don’t want your dog to learn the quickest way to get a treat is to break his stay.

- Decide on your criteria before you start training. Are you going to allow your dog to change position (say from a sit to a down) as long as stays in that spot? If you are not going to compete, this is purely a matter of personal preference. Remember for long stays, a “down” will be easier on your dog. Most dogs are less likely to break a “down stay.”

- Short training sessions! Stay is BORING! Don’t make your dog do it over and over again for an hour. You will both get bored. Take play breaks and just work on it for a couple minutes (or one long stay if you are at that point).

Duration

In class, you usually only work up to your dog staying in position for about the count of ten. But if you used that method to get your dog to do a 10 or 20 minute stay, you will be working on it for the rest of your dog’s life.

Obviously no one wants to do that. Instead, try “doubling minus one.” So, if you dog was staying nicely to the count of ten, try seeing if he will stay until 19 (double minus one). Reward him one time midway through (14 or 15). And then reward and release at 19.

Remember, you are only working on duration, so stay near your dog the whole time. But be sure to vary your position. So, stand in front, stand next to, sit in a chair. These are all things that can cause a dog to break if they are not use to it.

Using a stopwatch at this point instead of counting will keep you more accurate and allow you to know if your dog really is getting better.

Note: Don’t always make it harder. Throw in some short stays here and there. Why? Because if it continually gets harder some dogs will “give up” or refuse to keep playing. Would you keep doing math problems correctly if you teacher told you every time you got one right it was going to get harder and harder? After a while, probably not. It will differ for each dog, but it’s a good rule of thumb to throw short stays into the mix while training.

What if my dog breaks his stay?

If your dog fails three times in a row, you are asking for more than he is ready for and you need to lower your criteria – so release him earlier. Pay attention to about what time he is breaking and release him before that time. Then, try to see if he can stay at a time in between where he was successful and when he failed. So, if he failed at 5 minutes but was successful at 2.5, try 3.5 or 4, then continue to build from there.

Distance

Distance is usually harder than duration. As soon as you leave, most dogs want to follow. You can work on building your distance in the same way you did duration above. Just remember that you are not working duration with distance at this point, so come back immediately and reward/release your dog.

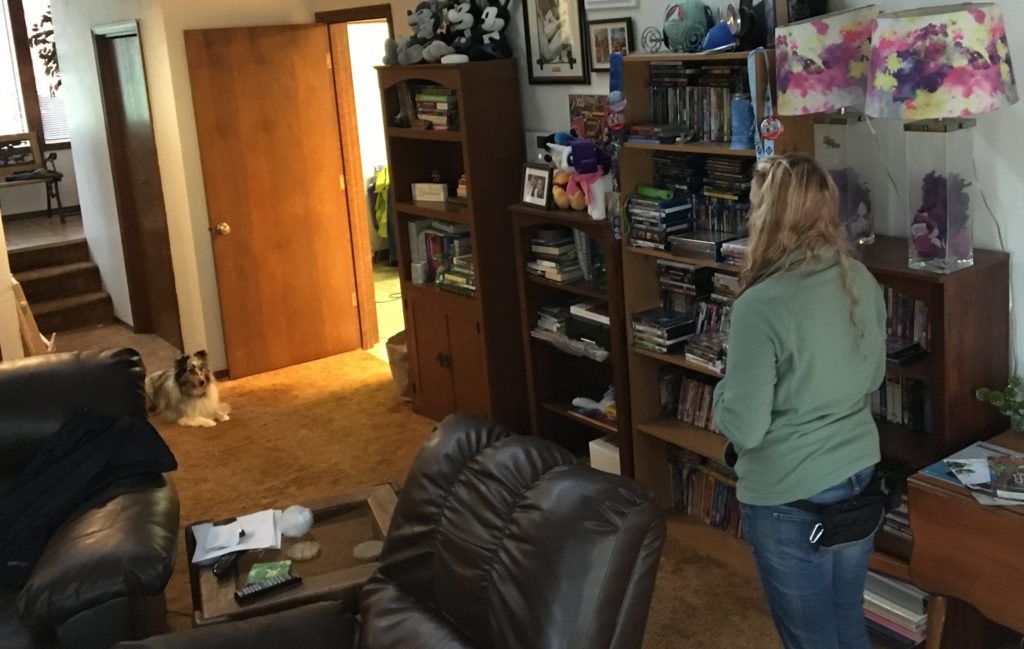

Once you can go across the room and your dog stays, it’s time to see if he can handle you leaving for a fraction of a second.

When you are able to leave the room, turn a corner and go out of sight, etc., you can start adding duration. A good way to do this is to go back and reward your dog immediately but don’t release him. Instead, move away again and then come back and reward/release.

Be sure to vary it each time, so sometimes you disappear from you view, sometimes you may only go a few feet, etc. The more varied you are, the better!

What if my dog breaks his stay?

The same rule applies here, too – if your dog fails three times in a row, you need to make it easier. Go back a step or two in your distance to where your dog was successful and try it again. When you are ready to make it harder, pick a point that was in between where your dog was successful and where he last failed.

Slowly start combining distance and duration. Do not immediately try to do an out of sight 20 minute stay. Your dog will most likely fail. Instead, maybe try a two minute stay with you ten feet away and see how your dog does.

Distractions

For most dogs, this is the hardest part, and this is the hardest to train. “Proofing” your stay means teaching your dog that no matter what happens around him (short of something life threatening), he needs to stay in that position.

Build slowly! I can’t stress this enough! Before now, you have been working your dog in a very controlled environment with no distractions. He may be doing a “sit stay” with you out of sight for 20 minutes, but that’s because he hasn’t had anything to make him want to move.

So, to start adding distractions, remember not to work on distance or duration at the same time to begin with. Instead, you are going to present a distraction, reward your dog for not moving and then release him AFTER you remove the distraction. You do not want the presence of the distraction to mean you are going to release you dog, so this is important!!

What do I mean by starting slowly? Start with something your dog doesn’t find that interesting. Maybe another family member walking by. Or the TV on. Or a toy (not being thrown, just holding it). Or squeaky a toy. Basically, anything that is a bit of a distraction but not your dog’s favorite thing on Earth.

Build up slowly to:

- Tossing a toy

- Tossing a treat

- Kids walking/laughing/running by

- Other dogs

- Other animals (cats, squirrels, etc) – this is hard!

- People running

- Cars (this can be hard for dogs that like to chase, for some dogs it’s no big deal)

What if my dog breaks his stay?

Just like above, if your dog fails three times, that distraction is just too hard for him. You need to find a way to make it easier. For distractions, there are a few things that make them easier or harder:

- Distance from your dog (a ball rolling by right under his nose is harder to leave than a ball ten feet away)

- Speed (rolling a ball slowly versus throwing it / kids walking versus running)

- Noise (loud noises can be harder for some dogs, especially exciting tones, laughter, screaming, etc.)

Knowing this, you can tweak your distractions to make them easier if your dog fails, and then build back up to the spot where he failed.

Putting It All Together

Once you have proofed your stay with distractions, you can start throwing in duration and distraction, separately at first- remember, you may have to go back a few steps and make it easier. Finally, start working on all three at once.

It’s a lot of work, but stay is a very important cue for all dogs to learn. If you do this, you will have a rock solid stay, even if the cat races past your dog, out the door and after a kid on a bike with an ice cream cone.